I really will get back to blogging about kidlit again soon, I swear. Meanwhile, some more history that I am really, really excited about.

There have been some amazing books on Chinese history published recently. It's enough to make me want to go back to college so I can drink a lot of coffee and discuss these bad boys with people who know a lot more than me about this stuff.

First up is the utterly fascinating and extremely readable The Long March: The True History of Communist China's Founding Myth by Sun Shuyun

In 1934, China's Communists, on orders from Moscow, were set up in Soviets. The largest and strongest was in Jiangxi province in south-east China. Chiang Kai-Shek's troops (who would rather fight commies than the encroaching Japanese) were closing in on all sides. The Soviet was doomed. On October 15, 1934, around 100,000 soldiers and Communist Party administrators broke through Chiang's lines and fled. They walked for 6,000 miles-- across mountains and rivers, grasslands, swamps and deserts, battling Chiang's troops all the way. It was here that Mao Zedong rose to power.12 months later, the 8,000 survivors reached Yan'an in north-west China. It was there that Mao rebuilt the red army to lead them to victory over Chiang's troops and, on October 1, 1949, found the People's Republic of China.*

So goes the story, the myth, the legend of the Long March. When the going gets tough? Think of the Long Marchers and all they endured so that the Party may survive. And, on the surface, this accounting of events is completely accurate, if glossed over more than a wee bit.

As Sun says:

Mao's foresight [in Yan'an in documenting the Long March] was quite extraordinary. To think of turning the Long March, which was essentially a retreat, into a glorious victory, was itself a stroke of genius. To be able to make it the founding legend of Communist China showed a political acumen, a gift for propaganda, and an optimism and self-assurance that few possess. p. 192

Part history and part travelogue, Sun set out to retrace the steps of the Long March, talking to survivors and veterans on the way, to get a sense of what really happened. She shied away from the higher-ranking officials that everyone talked to and sought out the foot soldiers who made up the bulk of the marchers. The result is an amazing account of the Long March and a story that hasn't been told before.

The myth and legend that is fed to Chinese school children is the same story told to Western audiences as well, mainly due to Edgar Snow's best-selling book Red Star over China: The Classic Account of the Birth of Chinese Communism, based on his time spent in the Yan'an base as Mao rebuilt his army.

Here Sun explores the major battles that Chiang's troops won, so were erased from the history books. She follows the women's regiment and the tragic Western Legion, left to die in the Xinjiang desert. Where the story goes that the 12,000 who were lost were lost to battle, starvation, and exposure to the elements, Sun also uncovers the loses due to inner-Party purges (which would become a mainstay of the Party for the following decades) and desertion. She tells the stories of the kids who joined because they were promised pork every day. Of the young men kidnapped from their villages and forced to join up.

One example of the new light Sun's work sheds on the Long March is the story of Luding Bridge. Most accounts you read will tell of Luding Bridge-- 300 years old, 101 meters long, and 60 meters about the torrid Dadu River, 13 irons chains and a plank flooring. Here 22 men held off Nationalist troops, with more closing in from behind, as they crossed the bridge. Most of the planks had been torn up and the remaining ones were set on fire. Due to several posters and movies, this is the most famous of the Long March battles. But, as one military historian in Beijing tells Sun, "You call that a battle? Just a couple of men fill into the river, and it was over in an hour."

She went to the bridge and talked to the villagers that were there. There were only a few soldiers in the bridge house with malfunctioning rifles. They fled. Most of the planking was still in place and it wasn't set on fire. It wasn't much of a battle, and it was over in an hour.

But still, I couldn't cross that bridge (and Sun had very real difficulty doing so). They did have to crawl across the chains at the end. It is nothing to scoff at.

The story that Sun uncovers about the Long March is more believable and more tragic, but it doesn't lessen what these people achieved or the terrible awesomeness of that year. If anything, it makes it more powerful, for the legend is true and the myth is real, even if the details aren't pretty or nice. I highly recommend this book to anyone with even a passing interest in Modern Chinese history or politics.

*I got my facts from: "Long March." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. 6 Aug. 2007 <http://library.eb.com/eb/article-9048863>.

Another amazing, but more academic book is Mao's Last Revolution by Roderick Macfarquhar and Michael Schoenhals.

Have you ever seen a picture of masses of young people hoisting copies of Quotations From Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (aka Mao's Little Red Book)? That was the Cultural Revolution.

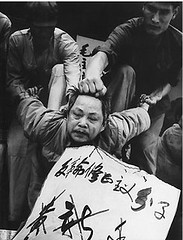

Concerned about losing his power base and his place in history, Chairman Mao launched a major purge of the Communist Party at the Eleventh Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee in August of 1966. Schools were shut down and China's urban youth were mobilized to keep the revolutionary spirit alive. They were told to bring down the four olds. While Mao kept the party in turmoil as he purged person after person, the Red Guards (the mobilized youth) tormented the urban landscape. They arrested and tortured anyone without a proper class background.

Red Guards overthrew the Party offices across the country. Many Long Marchers were blacklisted. Innocent people were purged, tortured, or killed. Several hundred thousand people were killed. Red Guard factions turned against each other for full scale civil war. The populace, the government, and the army were all deeply divided. In 1968, Mao sent them to the countryside, theoretically to learn from the peasants, but really to cool their heels for a bit, as his revolution had gotten way out of control. (Ever see Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl? She had been sent down to the countryside. Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress covers this as well.)

Despite this the Cultural Revolution really only ended with Mao's death in 1976. Then, Madame Mao's notorious Gang of Four was arrested and convicted and life tried to go on as normal. It was hard though, as business and the economy had been seriously disrupted for a decade. If schools were open, students only denounced teachers or memorized Maoist doctrine.

Mao's Last Revolution is the first academic-level full exploration of the Cultural Revolution. It's depth and level of insight is staggering. The authors have made full use of sources as recent as Jung Chang and Jon Halliday's Mao: The Unknown Story as well as recently opened archives in China. I think it would have been helpful to have a detailed timeline (I almost started making one to keep things straight). I greatly appreciated the glossary of names included in the back. I would not recommend it for the casual reader (try Red China Blues: My Long March From Mao to Now by Jan Wong for an easier read) but the student of modern Chinese history or politics would be seriously remiss to not have this on their shelves.

Sources:

"Cultural Revolution." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. 6 Aug. 2007 <http://library.eb.com/eb/article-9028164>.

"Red Guards." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. 6 Aug. 2007 <http://library.eb.com/eb/article-9062942>.

No comments:

Post a Comment